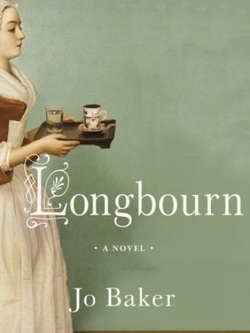

By Jo Baker.

Alfred A Knopf, 2013. 332 pages.

Hardcover. $25.95

Jo Baker’s Longbourn. A Novel retelling Pride and Prejudice from the servants’ perspective is more than an Austen spinoff. The Longbourn maidservant Sarah’s consciousness shifts how most Austen lovers have enjoyed Pride and Prejudice. The characters loved, loathed and sometimes scorned take on different perspectives. Sarah scrubbing Elizabeth’s boots “all stuck and clabbered with mud. Elizabeth’s were always the worst” (183), gives a new insight. Like Darcy, readers admire how Elizabeth walks though muddy fields, but never think (nor do the Bennets) who cleans the petticoats and boots. Mr. Collins, still unctuous, sees and is kind to the servants. To other characters in the novel, Sarah feels invisible, “a ghost –girl who can make things move, but cannot herself be seen” (198). Mrs. Hill’s perspective shows the young Mrs. Bennet whose five births (and one miscarriage in the fascinating back story) make her vulnerable.

Empathy is the main difference between Baker’s novel and Austen’s. Mrs. Hill worries what will happen to the two serving maids when Elizabeth and Jane marry and leave Longbourn. The servants’ narrative is now more important than the ruling family. The latter provides merely a background (a meta-fiction, like John Gardner’s Grendel), with Mr. Bennet drinking Madeira in his study while his daughters whirl noisily about, leaving their petticoats and chamber pots to be taken care of. As if to answer the Austen’s critics for not referencing the Napoleonic Wars, Baker focuses more on the militia. Wickham is a swaggering soldier; Denny and Carter are just as foolish, and surprisingly the very minor character Chamberlayne plays not only a significant part but pushes the theme of empathy.

Chamberlayne’s role demonstrates one of Jo Baker’s strategies, which according to Baker’s agent, Clare Alexander, is “analogous to that of the plays Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead and Hamlet—the servants are a jumping-off point for the tale, and then become characters in their own right “. Austen mentions the Bennet footman once: “Mrs. Bennet was prevented from replying by the entrance of the footman with a note for Miss Bennet” (30 emphasis mine). The heading of Baker’s novel --each chapter bears a quotation from Austen’s novel, except the war chapters-- when James’ role begins—states “… the entrance of the footman” (Baker 21). Hence the creative leap of James (the footman) observing Chamberlayne tricked out in a lady’s gown”(199-200). Lydia then asks James: “Did you see? …Did you see Chamberlayne?”(200). Austen gives Lydia’s breathless recounting of all the fun during their sisters’ absence: “We dressed up Chamberlayne in woman’s clothes…Lord! How I laughed! “ (Vol. 11.Chapter Sixteen 221). Baker’s Chamberlayne demonstrates the Bennet girls’ foolishness and the irresponsibility of the militia whom James (a seasoned soldier) sees merely playing at war.

The empathy theme features once more with Chamberlayn. Ending Chapter X11 Vol 1. Austen includes a minute detail: “several of the officers had dined lately with their uncle, a private had been flogged” (emphasis mine). No one reacts to the news, but in Longbourn, Sarah witnesses the private’s flogging, and one of the soldiers watching the 20 lashes and looking queasy is Chamberlayne (78) who does nothing. Sarah however, horrified, says, “she should go back, put herself between [the private] and the pain; they would have to stop” (79). Later, fifty lashes figure into the narrative, recalling Chamberlayne and the clever overlapping of James’ life with the Bennets.

Reading reflexively, Baker’s readers forge connections. Chamberlayne, or images like James’ seashells (64,149, 253), or words like “practical” (292, 299, 301) combine James’ experiences in the Peninsular War with his life at Longbourn. Reflexive reading and metafiction make Baker’s book remarkable. The book that Elizabeth loans Sarah pre-Pemberley days, Richardson’s Pamela is significant. Fielding’s novel Tom Jones has certain echoes in one of the back-stories, and the name Bennet is thought to come from Tom Lefroy’s favorite novel, Tom Jones. Jane Eyre also comes to mind, first when Sarah looks longingly out side Pemberley to the expanse of sky (313) reminiscent of Jane Eyre ‘s looking beyond Thornfield’s confines, and then trudging through the moors. Tess of the D’Urbervilles’ pursuit of exhausting jobs is another echo. Elizabeth Darcy has no concept of what it must be like to lead these girls’ lives. When Sarah tells her mistress she is leaving, Elizabeth’s questions are telling: ”Where will you go Sarah? What can a woman do, all on her own… and unsupported…?” Sarah replies ”Work…. I can always work” (312).

The hard labor and empathy theme develop from Baker’s own background, whose family a few generations back was in service. She would never have attended the ball but be “stuck at home with the sewing”. Educated at Oxford and Queen’s Belfast, Baker captures both upstairs and downstairs. The fun of words like “gallinies” and “lubber fiend” is unmatched in any Austen spin-off, and Longbourn has been translated into eight languages, with six figure film rights. Hearing this, Baker,“went off and planted a hedge just to keep herself grounded”. To misquote Mr.Knightley “Nicely done Jo, Nicely done”.